I’m fascinated by the game of mirrors and metalinguistic reflections reverberating from the use of art inside art inside art inside art, and all the implications and possible interpretations that result from this spiraling labyrinth. More precisely, this post is about famous paintings that feature in movies either as a direct element of the plot, or, more subtly, as an aid to help compose the fabric of the subtext. I’ll cover 3 interesting instances of clever uses of famous works of art and artistic style in the movies, which always cause a jolt of pleasure in the viewer who recognizes them, and, as a consequence, is able to connect the dots and understand the references.

1. The Skin I live In, by Pedro Almodovar, 2011. Let’s start with this brilliant Almodovar classic, which was heavily criticized when it first came out for its alleged shift of style from what the director had been famous for. Well, if these critics meant the movie adds layers of complexity to Almodovar’s previous works, I couldn’t agree more. However, if they are implying the movie was not funny, I don’t think they got it. It’s hilarious, although in a somewhat dark way. In addition to the humor, one important aspect of the movie is the theme of the contrast between culture and nature, between what is innate and what is fabricated and handed down by civilization; how far can one go to change what is considered natural? Without going into too much detail about the plot of the movie, let’s just say it’s about a surgeon who thinks it’s OK to recreate the human skin in order to improve it. And he tests his theory on an unlikely guinea pig: the man who allegedly abused his daughter, and whom he has turned into a woman, through an unauthorized gender reassignment surgery! Too weird? Maybe. But the point here is to discuss the symbolic meaning of the painting that decorates the surgeon’s mansion in Toledo, and keeps popping up in the scenes where he goes up and down the elaborate staircase: The Venus of Urbino, by Titian, 1538. This painting summarizes the main theme of the movie: the idealization and beautification of the real world. In this case, a beautiful goddess, with flawless white skin, concocted by an artist, conveys the impossibility that she could be recreated outside of this imaginary world. She will not leap off the painting and exist in real life.

2. Skyfall, by Sam Mendes, 2012. By far my favorite 007 movie. Everything works perfectly to make this a classic: action-packed opening scene, dreamlike credit sequence showcasing Adele’s song, a lot of fighting and shooting throughout, stunning locations (London, Istanbul, Shanghai), sophisticated dialogue, superb acting. And, as the underlying theme, we are to led to confront the universal and always worrying issue of the inexorable passage of time and how human beings cope with it. The main theme is made explicit in an anthological scene (see video clip below) where an aging 007 meets his new and young quartermaster: Q. They are both at the National Gallery in London contemplating Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire, 1838, which depicts an old ship being tugged somewhere to be destroyed. These are the best lines of the blistering dialogue that ensues:

Q: Old age is no guarantee of efficiency.

007: And youth is no guarantee of innovation.

Do I need to explain anything else?

Q meets James Bond:

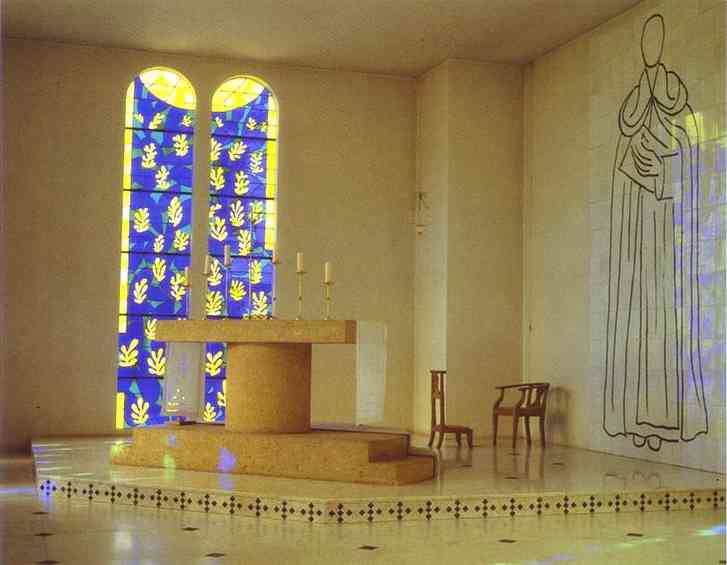

3. Mean Streets, Martin Scorsese, 1973. In this movie the symbolism does not come from showing a specific artwork. However, you can tell the cinematography and art direction are heavily influenced by the style of Caravaggio. You seem to be watching the application in movies of Caravaggio’s artistic principles: Scorsese, just like his baroque predecessor, depicts the contemporary world (1973 New York) of the Italian Mob, shown in beautifully staged scenes where the technique of chiaroscuro or tenebrism predominates. Every scene seems to have the lighting coming from a single or, sometimes, two naked light bulbs carefully placed to focus on the foreground, where the action is taking place. The background is dimmed or blackened in shadows. The characters seem to behave as modern versions of Caravaggio and his mates themselves, rambling through the dark streets of VII century Rome (represented by 1973 New York) after nightfall, going to taverns (bars, and pool joints) and whorehouses (stripclubs). They are constantly gambling, getting involved in brawls and fights, some of those – in the movie – nicely choreographed to the Rolling Stones or the Beatles songs. In addition to that, you hardly ever see a shot without an element of the Catholic iconography featuring prominently in the setting: images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, crucifixes, photos of the pope and the interior of churches themselves. What would we call this? Post-modern baroque?

Let us know what you thought of this post: write your feedback on the comments section of the blog.

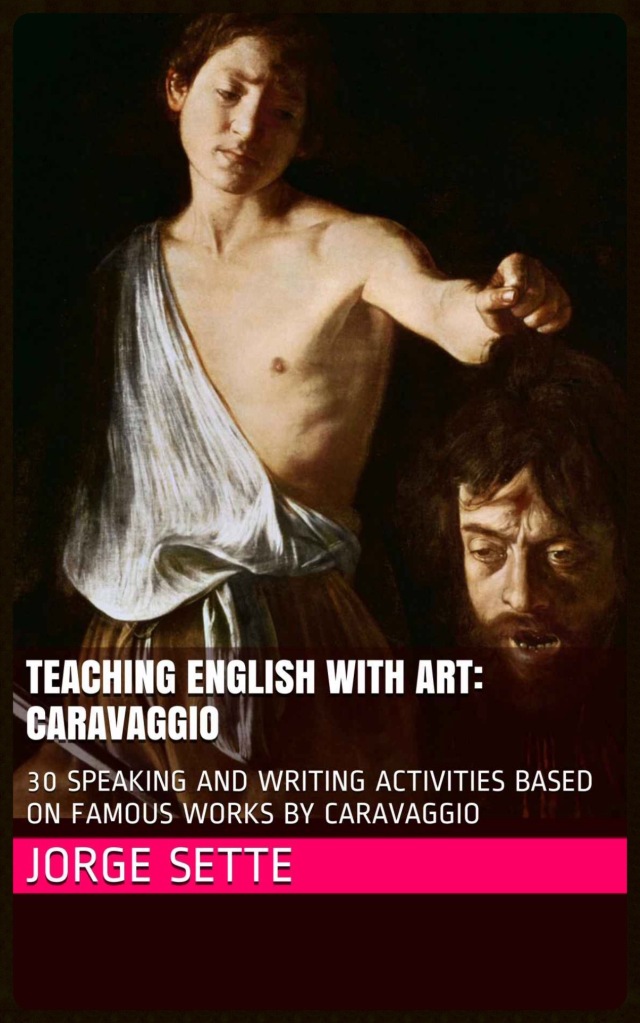

NOTE: If you are into art, you may consider checking out our eBook series TEACHING ENGLISH WITH ART: http://wp.me/p4gEKJ-1lS

Au revoir

Jorge Sette.