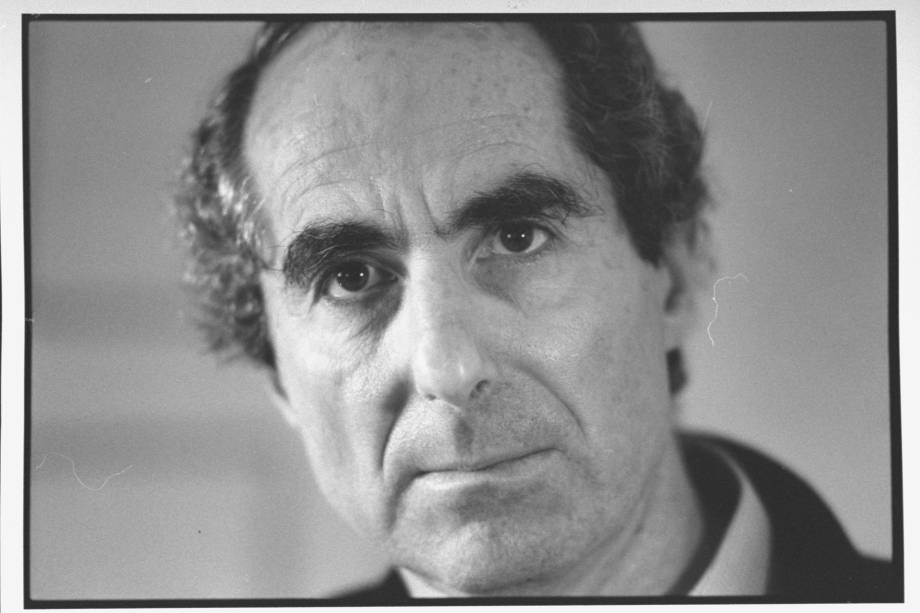

“Everybody else is working to change, persuade, tempt and control them. The best readers come to fiction to be free of all that noise.” Philip Roth

“Everybody else is working to change, persuade, tempt and control them. The best readers come to fiction to be free of all that noise.” Philip Roth

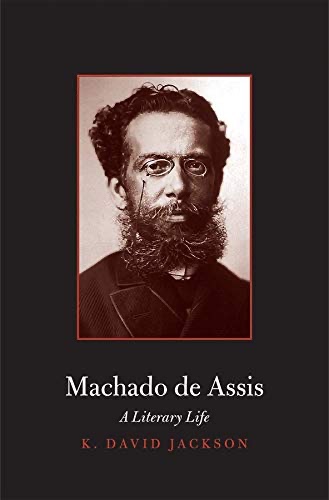

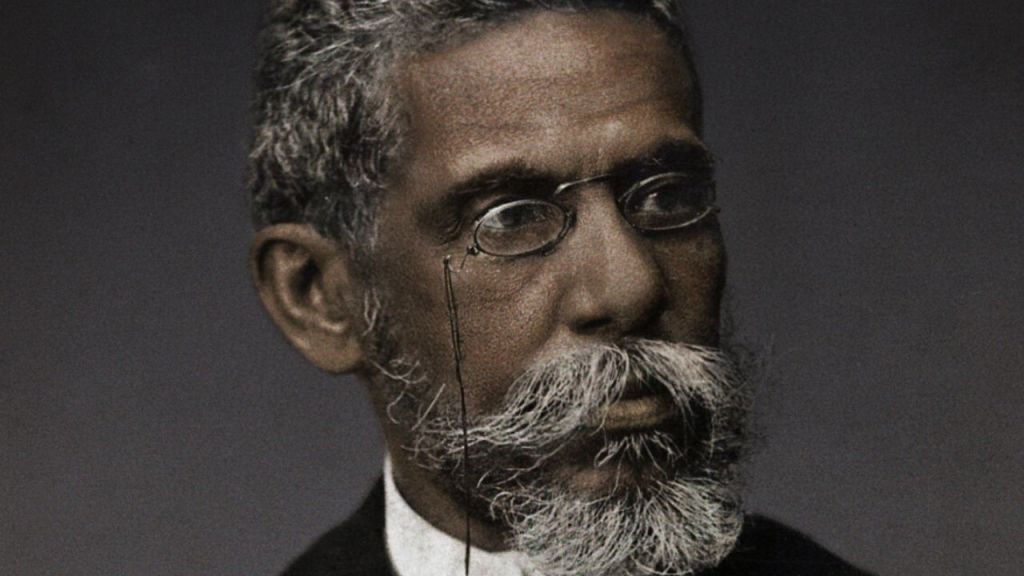

In his in-depth work, K. David Jackson, Professor of Portuguese at Yale University, focuses on the oeuvre of Machado de Assis, rather than on more personal aspects of his life. If, on the one hand, you wish you’d get to know more about the man behind some of the greatest works of the Latin American literary canon, Jackson’s choice is understandable. Machado was a very private person, who led a rather uneventful and quiet life, totally devoted to his artistic objective: the construction of a philosophical and fictional world.

This detailed work by K. David Jackson isn’t, therefore, your typical biography, but a fascinating study of Machado’s output, illuminating unsuspected aspects of his fiction and acquainting the reader with hidden facets of his creative process.

Here are some of the most engaging points made in the book:

1. Biographical landmarks: Machado de Assis, known as the Wizard of Cosme Velho (the neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro where he lived), was the co-founder and first president of the Brazilian Academy of Letters (1897). His most famous works are the Carioca Quintet (a set of five novels published from 1881 to 1908: The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas; Quincas Borba; Dom Casmurro; Esau and Jacob; Counselor Aires’ Memoirs). He died in 1908 at the age of 69. His image was used on a Brazilian banknote in 1988, and he was the featured author at the International Literary Festival Party of Paraty (FLIP) in 2008, to celebrate the centenary of his death.

2. His importance: According to Jackson, Machado’s writings ought to be placed alongside the works of Dostoevsky, Gogol, Hardy, Melville, Stendhal, and Flaubert.

3. Innovation: Having started off as a romantic writer and progressively become associated with the Realist artistic movement in Brazil, Machado is said to have anticipated the modernist narrative features found in Proust, Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Camus, Mann, and Borges.

4. Features: Machado’s work is hybrid and cannibalistic (intertextual). Through extensive reading, he assimilated and digested an incredible amount of information on Western culture as a whole (arts, music, philosophy, and literature), and based on these sources produced a very original body of work, using the social context of the city of the Rio de Janeiro during the Empire as a means to discuss and represent, mainly through parody and satire, universal truths and human dilemmas.

5. His most important works (such as The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas and Dom Casmurro) feature unreliable character-narrators, whose hallucinations dreams and obsessions are said to anticipate Freud’s psychoanalytic theories.

6. Theater and opera: These are among the main influences in the construction of the fictional space of Machado de Assis. Rio de Janeiro hosted a great number of European theater and opera companies in the 19th century, which allowed Machado to be exposed to a lot of comedic operas (opera buffa) and plays, which are not only frequently referenced in his fiction, but are also woven into the fabric of his works.

7. Shakespeare’s Othello: the classic story of the Moor who kills his wife Desdemona out of jealousy is reflected in the feelings – if not the actions – of important protagonists of Machado’s fiction. Othello is, for example, one of the main inspirations of Bento Santiago, the character-narrator of Dom Casmurro, whose insecurity and obsessions prompt him to write his memoirs as a way of persuading himself and the readers that his wife, Capitu, had an affair with his best friend Escobar, bearing an illegitimate son, Ezequiel.

8. Social Darwinism and Positivism – dominating scientific theories at the time – were strongly criticized and ridiculed by Machado, especially through the fictitious philosophy of HUMANITAS, summarized by the motto To the Victor, the Potatoes, created by the mentally unstable character Quincas Borba, who first appeared in The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas. He later made a comeback in the novel Quincas Borba (although, in typically oblique Machadian fashion, he’s not the protagonist of the book).

9. Main themes: Machado’s work is a profound depiction of Rio de Janeiro society during the Empire. This microcosm, however, is used by the author only as a familiar context for the highlighting of universal themes, such as legitimacy, chastity, honesty, hypocrisy, adultery and cruelty, which receive a modernist treatment in his hands.

If you haven’t had the chance to read Machado de Assis yet, K. David Jackson’s book will surely whet your appetite. For those, like me, who have read and reread Machado on a regular basis, Jacksons’ work was a surprising and welcome source of new interpretations of the familiar novels and short stories the Brazilian author is most famous for.

Jorge Sette

It’s exciting to have complex scientific concepts explained in everyday language, in a way that makes you acknowledge the relevance of the topic and understand how it affects your life. There is a line of great books that do that. In general, they belong to a genre called ‘popular science’ books.

The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddartha Mukherjee – a cancer physician and researcher as well as a stem cell biologist and cancer geneticist – goes way beyond that narrow genre definition, though. With the objective of discussing “the birth, growth and the future of one of the most powerful and dangerous ideas” in science (the gene), the author explores historical facts and tells personal anecdotes about the main people involved in the narrated events, and bravely includes information about his own Indian family history – with its many cases of mental illnesses – to illustrate points and, ultimately, to justify his interest in the subject.

Containing a great number of literary and movie references, and using language that becomes poetic and evocative at times, the author does not hesitate to apply clarifying metaphors to help us understand processes and results. The Gene, therefore, must be categorized as a hybrid text, with strands of history, science, biographical data and literature tightly interwoven in a fascinating whole, in which issues of heredity, illness, normalcy, family and identity are discussed.

In this post, we list and summarize 10 key lessons we have learned. Of course, we will be simplifying and reducing much of the fascinating content you will find in the book.

1. Darwin and Mendel: The science of genetics started off in the middle of the 19th century, with the development of Darwin’s theory of the origin and evolution of species (based on the idea of mutations, natural selection and the survival of the fittest) and the first heredity experiments carried out by Gregor Mendel in his pea garden in the backyard of the Augustinian abbey where he lived. Mendel discovered that heredity was handed down through discreet units, which were much later – in 1909 – called genes.

2. Eugenics: In 1869, Francis Galton coins the term “eugenics,” in his book Heredity Genius. Eugenics misused new genetic discoveries, helping create distorted and evil racial hygiene government policies, which enabled the setup of special asylums and the submission of mentally ‘feeble’ women to sterilization by force in the 1920s in the US, and the promotion of Nazi ideas about the purification and preservation of the Aryans as a superior race during the 1930s and 40s, with the extermination of millions of human beings.

3. The gene: If the atom is the basic unit of the matter and provides an organizing principle for physics, genes represent a similar unit in biology and provide similar organizing functions. Genes are parts or stretches of chromosomes – “long, filamentous structures buried within cells.” Human cells contain forty-six chromosomes: 23 inherited from one of parent and 23 from the other. They provide recipes (instructions for processes: basically the making of different kinds of proteins) and regulate all the work done by our cells. They are located in the nucleus of the cell.

4. Chromosomes: Chromosomes are made up of a special molecule called DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), composed of sugar, phosphate and four kinds of bases (guanine, thymine, adenine and cytosine). The DNA structure – discovered by Watson, Crick, Wilkins, and Franklin in 1953 – consists of a double helix format with two strands linked by the bases.

5. RNA (ribonucleic acid): RNA is another molecule, similar to the DNA in structure, but with a single strand. It copies stretches of code from the DNA and serves as a messenger, carrying instructions from the genes located in the nucleus to the cytoplasm – the liquid part of the cell outside the nucleus – where proteins will be assembled according to the RNA code. Proteins compose most of the structures of our tissues, signal the initiation of processes and accelerate chemical reactions in our bodies. They rule.

6. Diseases associated with genes: From 1978 to 1988 a series of disease-linked genes were mapped. There are basically two kinds of gene-related diseases: monogenetic (involving one gene, such as cystic fibrosisand Huntington’s disease) and polygenetic (involving the coordination of a number of genes – most diseases, including cancer and schizophrenia, belong in this category). Besides, the effect genes have on the development of diseases is influenced by the level of penetrance. This means that different gene-related diseases are more likely to express themselves than others. The environment also plays an important role, working as a trigger to some of the diseases.

7. The ‘gay gene’: As of 1993 scientists started wondering if homosexuality could be directly linked to a gene. While there is evidence that there is a strong correlation between sexual orientation and the presence of a gene or a group of genes located in a certain region of the X chromosome, no one knows for sure how the process of formation of sexual identity is carried out. There may be other regulators scattered across other parts of the genome (see definition below); there’s no doubt that powerful environmental inputs or triggers are also at play here.

8. Race: Genetic studies disprove the mythical concept of race. Studies show that there is more variation within a “race” (85% to 90% percent of the level of total diversity of the human genome) than between the so-called “races” (only 7%).

9. The genome: The genome is the collection of all genes (with annotations, footnotes, and references) found in a species. In human beings, it amounts to three billion base-pairs, divided up into 21,000 to 23,000 genes (differentiated parts or stretches of the whole genome). In the year 2000, a draft sequence of The Human Genome Project, an international initiative to map and sequence the entire human genome, was announced.

10. The future: In the past years or so, we have developed new technologies which allow us to manipulate, re-engineer and edit genomes. We are at the stage where scientists are able to alter the human genome permanently, but we still don’t know all the moral, ethical, and physical implications of that. One of the objectives of this book is to bring more people into this interesting discussion. For the first time in history we will be creating a new species of humanoids. It’s, therefore, essential that all kinds of voices in the global community express their concerns, present their cases, and share their perspectives before we go down this road, as the process may be irreversible.

Siddartha Mukherjee’s previous book – The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer – won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction and the Guardian First Book Award.

Jorge Sette.

Jorge Amado (1912-2001), one of the most popular and internationally known Brazilian authors, started his career writing realistic books that carried a biting criticism of the economic elites and their exploitation of the working classes and the poor. This Marxist phase characterized the first of his works. After the publication of Gabriela, Clove and Cinnamon in 1958, however, his novels became more populist and satirical, with a stronger focus on the sensuality and picturesque aspects of the afro-Brazilian culture of the author’s native state of Bahia, located in the northeast of the country. The author was harshly criticized by many for having changed his tone.

With Tent of Miracles, first published in 1969, one could say that Amado managed to strike a fine balance, providing a serious examination of Brazilian socio-economic issues and highlighting the hedonism and colorfulness of the Bahian culture, with its stunningly beautiful mulatto women, the freewheeling sensuality of its people, their lively songs, and dances and the prevalence of African-originated religions and cults.

The Themes

Tent of Miracles is a strong satire on the parochialism of the Brazilian intelligentsia – which needs validation from developed countries, especially from the US, before appreciating local talents in all areas of art and knowledge. The novel is also an inspired ode against racism, praising the power and beauty of miscegenation. In that respect, we can say that the themes of the book are more relevant than ever in today’s global context of generalized xenophobia, racism, and prejudice against diversity.

The Plot

The story kicks off when a Nobel Prize-winning North-American scholar, D.J. Levinson, comes across some forgotten books in the library of Columbia University and decides that their author is one of the best anthropologists he’s ever read. The racial considerations and the detailed description of the customs and “folkways” of the racially-mixed people of Bahia found in those four dusty volumes deserve to be known and discussed by the global academic community. The author, a black Brazilian called Pedro Archanjo, lived in Bahia for 75 years (1868 -1943), doing menial work in the streets of the city of Salvador (called Bahia at the time), destitute and unrecognized by his upper-class contemporaries. Levinson then comes to Brazil to experience first hand the theories put forward in the books and to promote their author.

Of course, the announcement of the arrival of the US luminary makes headlines in the biggest newspapers of Brazil. This arouses the interest and greed of the local authorities, intellectuals, and politicians, who wish to advance their own personal agendas, tapping into the newly-elevated status of Pedro Archanjo to scientific prodigy. It’s decided that the centenary of Pedro Archanjo’s birth – about to take place at the end of the year – deserves a fitting and official celebration in the city after all.

At this point, the lesser writer and poet Fausto Pena is hired by Professor Levinson to do research into the life and times of Pedro Archanjo, spanning more than 70 decades. In reality, Levinson’s main objective is to get Pena out of they way so that he can enjoy the pleasant company of the poet’s girlfriend, the journalist Ana Mercedes, an unashamedly social climbing mulatto beauty.

As a result, it is through Fausto Pena’s eyes that we get to know the story of Pedro Archanjo, despite all the gaps, incongruences and half-truths he gathers in his notes. We learn about Archanjo’s popularity among women, the innumerable children he fathered out of wedlock, his work as a runner for the School of Medicine and, finally, his rising awareness of the social conditions of the underprivileged people of Bahia, subject to all kinds of oppression, violence, and prejudice. Archanjo then decides to self-educate, write about race relations, and become a political militant.

Despite its important and political undertones, the story, of course, unfurls against the backdrop of a poetic and colorful Bahia, with humorous anecdotes and detailed descriptions of the rituals of the local afro-influenced religions, the local foods and spices, the dance and music. Jorge Amado kept many original African words in these passages – wisely kept in the translation into English – presenting a complete glossary in the back of the book.

The Characters

The characters of Tent of Miracles are not entirely realistic, but ironic representations of specific types that populate the Brazilian collective imagination. We can split them into the powerful (corrupt politicians, controlling newspaper editors, arrogant college professors) and the disenfranchised (the malandros, bon vivants, ruffians, drunks, gorgeous mulatto women, old wise men, and gold-hearted prostitutes).

Most of them, however, come across as a bit underwritten; they are not fully rounded characters. Pedro Archanjo, of course, personifies all the contradictions of a typical popular hero, as all his facets are praised in the Carnival celebration held in his honor at the end of the book: minor candomblé priest, vagabond, striker, runner of the School of Medicine (where he started his more formal education), heavy drinker, womanizer, teacher, sorcerer and writer!

The Style

Although the book has strong elements of magical realism, especially in the scenes that take place in the candomblé terreiros, the space where the afro-religions and cults have their rituals (devotees embarking in trances; divinities taking possession of their bodies; supernatural events occurring; myth and reality getting intertwined), most of the plot develops in a fairly realistic and straightforward way.

The Relevance of Tent of Miracles Today

Written during the first years of the Brazilian military dictatorship, the passages depicting the brutal repression by the police of the Afro-Catholic cults, the bloody raids against the terreiros, and the beating or killing of their members – which happened especially during the 1920s and 30s – can be interpreted as a fitful metaphor of the times.

The novel, however, does not feel dated at all, as its themes are still universal and very concrete. The irony made explicit in the story is that miscegenation deeply permeates the whole of Brazilian society, and, thus, the bigotry and racism of people whose mixed-race blood is either carefully hidden in the family past or even naively ignored are laughable and hypocritical. It’s time for Brazil – and other countries in the world – to bury the myth of white supremacy and come to terms with the fact that we’ll carry on living in an irreversibly multicultural, mixed and diverse society.

Jorge Sette

In his book Ernest Hemingway on Writing, Larry W. Phillips does a wonderful job of collecting the great author’s thoughts on the field of writing. Phillips draws from various sources including personal letters, books, novels, essays, commissioned articles, and interviews. Sectioning our post in the same way Phillips did with his book, let’s try to summarize some of Hemingway’s most interesting ideas on the topic.

What Writing Is and Does

• Good books are all alike in the sense that they feel true. Communicating genuine experiences to the reader is essential. It’s the writer’s job to convey to the reader feelings, sensations, and even the weather, as he narrates the experience he’s writing about.

• Literature is, after all, poetry written in prose and it should read like that.

• Good books may be reread as many times as the reader wishes: they never lose their mystery, there’s always something new to learn.

The Qualities of a Writer

• Writers need the talent of a Kipling and the discipline of a Flaubert. They also must be intelligent, honest, and disinterested.

• Writers must be able to detect anything that doesn’t sound genuine in their texts. Their minds need to work as radars to avoid artificiality.

• To write novels, writers need to have an inbuilt sense of justice and injustice. Otherwise, they had better be doing something else.

• Writers need to be fast learners. Knowledge of the world is an essential tool for this job.

The Pain and Pleasure of Writing

• You write for two people basically: for yourself (and you need to make it perfect) and for the person you love, so they can read it and share the experience.

• Hemingway says he never suffered when he wrote. He felt empty and horrible when he was not writing. This is the opposite experience of many other writers, as you probably know.

• Writing is a difficult and challenging process, yet, so rewarding. It’s a disease some people are born with.

• Sometimes a writer will need to reread something good he has written in the past to convince himself he can still do it, and then, will continue writing.

• Writing is an obsession. Maybe a vice.

• There are no rules to writing: it may come easily sometimes, and at other times it can seem almost impossible.

What to Write About

• Don’t write about your personal tragedies: nobody really cares about them. But you can use your hurt feelings to convey truth in what you are writing.

• A man has to have suffered a lot to write a really funny book.

• Writers should stick to what they know profoundly.

• Readers expect the writer to repeat the same story every time they pick up one of their new books. Don’t do that: the new book is not going to be as popular at the last.

• War is a good subject. Experiencing war can teach writers a lot. Some are jealous because, never having taken part in a war, they can’t write about it firsthand. Other good topics are love, money, avarice, and murder.

Advice to Writers

• At the beginning of your text, write one true sentence. The rest will stem from that.

• Write about what you really feel, not what you are supposed to feel. Only real emotions count.

• Remember the details of the experience that inspires you in order to pass on to the reader real feelings and sensations. Readers should relive your excitement.

• Listen carefully and actively when you talk to people, so you can understand their perspective and use it in your writing. Learn to put yourself in other people’s shoes.

• Hone your observational skills.

• To be truthful, you can’t put only what is beautiful in a novel. You need to add the ugly and the bad.

• Distrust adjectives.

• Write like Cézanne painted: Start with all the tricks and then get rid of all the artifice and bare the truth.

Working Habits

• As you are writing, stop when it’s going well. So the next day you feel energized about the task and pick it up knowing where you are going.

• When you are not writing, don’t think about it, try not to worry about your novel; do something physical or read other books. Let your subconscious work on it.

• Every time you start writing, reread everything you have written so far. When it begins to take too long to cover all the written passages, reread only the last few chapters.

• After writing a novel, give it a couple of months before you start rewriting it. Let it cool off. So it looks and feels fresh in your mind when you go back to it.

• Hemingway needed to be left completely alone to focus on his writing. He said writing, at its best, is a lonely life.

Characters

• Hemingway refused to write about living people. He didn’t wish to hurt anyone. Unless he deliberately wanted to.

• Use what you know as well as other people’s experiences to write fiction, but don’t make them recognizable. Invent it.

• Let people be people, don’t turn them into symbols.

Knowing what to leave out

• Hemingway compares writing to an iceberg: only the tip shows, but the underwater part is the knowledge the author has about what he’s writing, and it matters.

Obscenity

• Avoid slang (except if it’s needed in dialogue).

• Only use profanity that has existed for 1000 years. It may go out of fashion fast.

• Don’t use profanity merely for its shock value. Make sure it’s really necessary.

Titles

• It takes time to find a good title.

• A great number of good titles comes from the Bible, but they have all been taken.

Other Writers

• Other writers can teach you a lot.

• A selection of books every writer should read: War and Peace and Anna Karenina (Tolstoy); Madame Bovary (Flaubert); Buddenbrooks (Thomas Mann); Dubliners (Joyce); Tom Jones (Fielding); The Brothers Karamazov (Dostoevsky); Huckleberry Finn (Mark Twain); The Turn of the Screw (Henry James)…

• Authors should write what has not been written before or try to beat dead men (which means: write better than former writers on a certain subject).

• Hemingway thought War and Peace was the best book ever written, but that it would have been even better had Turgenieff written it.

Politics

• Do not follow the political fashions of your time. They are temporary and will wear off soon.

• There is no left and right in writing: only good and bad writing.

• Patriotism does not make good writing either.

• Don’t write about social classes you don’t belong to or don’t know deeply about.

• Writing about politics may get you a good job in government but it won’t make you a great author.

The Writer’s Life

• Writing is more exciting than the money you make from it.

• When writers make a lot of money, they get used to an expensive lifestyle and have to carry on making money to sustain it. That’s when they compromise.

• Good writers don’t keep their eyes on the market.

• Publicity, admiration, adulation or being fashionable aren’t worth it.

• Writers should be judged on the merit of their writing and not on their personal lives.

• Critics have no right to invade the writer’s personal life and expose it.

• Critics will find hidden symbols and metaphors in a text when they are simply what they are.

Please let us know your opinion about this post.

Jorge Sette

Even if the reader did not watch these shows when they first aired, there were reruns throughout the seventies, eighties, and nineties, and some of them can still be watched on cable TV and streaming services. Besides, most of them are available as DVD box sets.

Younger people may find it hard to believe we loved those shows. How could we stand the primitive and amateurish visual effects? How could we tolerate the bias against women, gays, blacks and other minorities? How could we sit still through the slow pace, and the lack of jokes and punch lines present every other second in today’s sitcoms?

Well, those were more innocent times, we were naïve viewers, we couldn’t anticipate the complicated nuanced plots, complex social analysis and great acting of shows like THE SOPRANOS, MAD MEN, BREAKING BAD or HOUSE OF CARDS. Those early shows were all we had back then, and the whole family gathered together in front of the bulky black and white TV set to watch them. Few families had color TV in the early seventies in Brazil. Besides, now and then, one of us would have to stand up and reach for the TV aerial to adjust it or pound on the top of the TV set to get the image to straighten up. Did I forget to say there were no remote controls either? Bad news for the couch potatoes.

These were the most popular shows among my friends in those days:

Lost in Space. This was by far the kids’ favorite show. When I was older, my mother explained the reason we were so into that show was that it featured a well-adjusted, loving family confronting the tough obstacles an ominous Universe put in their way. Could be. The aforementioned family – the Robinsons (any reference to The Swiss Family Robinson, the novel by Johann David Wiss published in 1812, is not coincidental) – sets off to investigate conditions to colonize a planet near Alpha Centauri, due to the overpopulation on Earth in the inconceivably distant future of ….1997!

Their trip would last 4 years, during which time they would remain frozen in suspended animation. However, many other nations were working on similar projects, competing with the US. Therefore, the wicked and ambitious Doctor Zachary Smith (Jonathan Harris), who worked for the US project as a psychologist, was hired as an agent by one of these competing nations. He carries the responsibility of sabotaging the mission. The problem is Doctor Smith gets trapped in the spaceship, the two-story disc-shaped Jupiter 2, seconds before it takes off, being forced to leave Earth with The Robinsons. The extra weight veers the spaceship off its original course and they get inevitably lost. He will be a burden to the family and their pilot, Major West, as they face innumerable perils in space or on the alien planets they sometimes land on. Rumor has it the producers’ plan was to feature the family patriarch Professor Robinson (Guy Williams, of Zorro fame) and his co-pilot Major Don West (Mark Goddard) as the stars of the show. But as the episodes developed, the focus shifted almost 100% to the adventures of Doctor Smith (played hilariously by Jonathan Harris), the male kid, Will Robinson (Billy Mumy), and their loyal Robot, who stoically took all the abuse heaped upon him by Smith. The trio simply stole the show. Smith was supposedly gay (and rather camp), but no one talked about it at the time, and there was never any fear that he could corrupt his young partner, Will. The visual effects were pathetic and look ridiculous by today’s standards. The settings and monster costumes are incredibly amateurish and silly too. But we loved the show.

I dream of Jeannie. Everyman’s sexual fantasy come true, there was never, however, a more innocent relationship between a master and his sexy slave than the one sustained by Astronaut Major Nelson (Larry Hagman) and the genie he finds imprisoned in a bottle on a desert island on the Pacific, setting her free.

Actor Barbara Eden, who played Jeannie, was at the height of her beauty and sensuality in those days, and, although the network decency guidelines wouldn’t allow us even a glimpse of her navel, she must have stirred the hormones of many a teenager and young man. Major Nelson, though, seemed immune to her attractions. We, on the other hand, were too young for those kinds of feelings and sensations. Girls loved the little doll house Jeannie lived in inside the bottle, while boys had the time of their lives watching the problems she caused Major Nelson by timing the execution of her magic tricks, accomplished by blinking her eyes and crossing her arms, to whenever Doctor Bellows (Hayden Rorke), the space program psychiatrist, was around.

The Time Tunnel. This show did what every school should be doing: teaching history in a fun and engaging way. This, of course, was far from the objective of the producers, who only came up with a clever premise to raise their ratings, without any noble educational purpose in mind. The show featured two scientists trapped in a time machine built by the US government in the shape of a tunnel, hence the title.

The machine gets out of control and the scientists cannot return to the present. Every episode would feature a story in which they’d land either in the future or the past. The episodes depicting important past events (the Second World War, the eruption of the Krakatoa and the sinking of the Titanic, among others) outnumbered the ones set in imaginary futuristic scenarios, which turned the series into great history lessons. We learned a lot from watching it, and had fun at the same time.

Batman. The most psychedelic show of the era, the 60s version of the Dark Knight was an explosion of color (for those who could afford color TV), unforgettable idiosyncratic nemeses (such as Catwoman, the Joker, The Riddler and The Penguin) and exciting fight scenes during which innovative onomatopoeic speech bubbles popped up on the screen (Pow! Plop! Bang! Craack!). The costumes worn by most characters were duly ludicrous and it never crossed our naïve minds that the whole thing was supposed to be a parody of the comic books. We took the adventures very seriously: the anthological death scene of Catwoman, falling from a tall building after dangling for a couple of tense minutes by the grip of Batman’s heroic hands before plunging into the void, depressed the most sensitive kids of the time. We all loved Catwoman, she was sexy and fun, who cared if she was evil?

Many other shows of the time were also popular, such as Land of Giants, Bewitched and The Monkees. Television evolved a lot in more recent years, and I daresay some of the new shows have way more quality than many of the movies we watch in theaters. I was lucky those silly shows coincided with my childhood and early teenage years: I was able to enjoy them fully without any sense of shame or guilt.

What was your favorite TV show of the sixties and seventies?

Jorge Sette.

“Look, everything the Communists say about capitalism is true, and everything the capitalists say about Communism is true. The difference is, our system works because it’s based on the truth about people’s selfishness, and theirs doesn’t because it’s based on a fairy tale about people’s brotherhood. It’s such a crazy fairy tale they’ve got to take people and put them in Siberia in order to get them to believe it.”

― Philip Roth, I Married a Communist

Philip Roth died on May 22, 2018, at 85. This is the last article I wrote about him:

Before you read this post, you must understand and accept that nothing about it is objective or detached. I’m a huge fan of Philip Roth, who is considered by many one of the greatest American writers. I love his books. From the first Philip Roth I ever read – I was 17 or 18 at the time, young and impressionable – I was hooked for life. The fact that it happened to be the outrageously funny and scandalous Portnoy’s Complaint undoubtedly had something to do with my obsession. So my disclaimer is this: partiality will color this article; I’m a pro-Roth kind of person. My plan in this article is to tear down ingrained myths about the life and work of this brilliant provocateur, in my own inartistic words.

1. Philip Roth was an anti-Semitic, self-hating Jew.

Have you ever read any of his books? The fact that he was Jewish pervades his work. His self-deprecating comments can only deceive the naive. He was very proud of his ethnicity and his family and friends, although he was far from orthodox or even religious. Roth was an atheist. The misunderstandings arise from his greater pride in being an American and his love for the fundamental (although perhaps more ideal than real) values the US stands for. He never took for granted the freedom and lifestyle that are the simple result of being born and having grown up in the geographic space that comprises the United States of America. Unlike the Anne Frank of his book The Ghost Writer, he had a childhood. And if he refused to be “a good boy” to be accepted, it’s because he believed that being a good boy made it even harder to fit in. You need to be outstanding, outrageous, infamous to break down walls and belong in the world of the goy.

2. Philip Roth wrote about his own life.

Of course, reality informed his stories, and reality is apprehended through personal experiences as much as from vicarious ones – from books we read, movies we watch, things that happen to our family and friends. So there’s certainly a lot of Roth’s own life in his stories, but these experiences are transformed by imagination; they’re not necessarily exact representations of things that happened to him or that he did himself. Everything is filtered through the powerful lens of language and fiction. Life becomes larger and its dark corners are illuminated by the spotlight of Art. Hyperbole, amplification, metaphors, and masks are all part of the process. You can’t put your finger on a single paragraph in any of his books and guarantee it describes something that really happened to him. Even the famous Nathan Zuckerman, who first appears in The Ghost Writer and continues to feature as either the protagonist or the narrator in many subsequent novels, isn’t a warranted alter ego. I’ll admit Zuckerman is the mask that most closely resembled the author behind it, but he’s not Roth. There are a couple of books, however, in which Roth dares to unmask himself and write about reality – as far as this is possible since experiences are based on memory and language, which somehow always transform them. One of these non-fictional books is The Facts: A Novelist’s Autobiography, written after a serious bout of depression caused by taking the drug Halcion for pain in his back. He wrote this short autobiography covering only the first 30 years of his life as a healing exercise, stripping himself as much as possible of his imagination and the usual masks. The second is the moving but never sentimental Patrimony: A True Story, a “snapshot of his father in movement,” as he states in the BBC documentary Roth Unleashed (which I strongly recommend), and a portrait written so he could remember his father in as much detail as possible. “I mustn’t forget anything,” was his mantra at the time. His father was dying of a brain tumor, and Roth realized he had the makings of a book – a tribute to the old man – in the notes he took at the end of each day, after coming home from the hospital where he looked after his father.

3. Philip Roth was a misogynist.

All I can say is Claudia Roth Pierpont (no relation to Philip), the writer of a very interesting book titled Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books, is a woman, and she strongly disagrees with the view that Roth hated women. She gives the reader great insight into his body of work, including the themes, language, characters, and masks explored in his novels, and she maintains his books probe deeply into the human soul and bring up everything, the good and the bad, and therefore include a wide spectrum of women characters. It’s not accurate to say that he always depicted women as shrews. Besides, who’s to say that the women depicted as shrews in certain novels are representative of all women? If he hated women, he must have hated men as well, or haven’t you met one of the most despicable and depraved heroes ever created in Western literature: Mickey Sabbath, the protagonist of Roth’s gripping novel Sabbath’s Theater?

4. Philip Roth was a misanthrope.

Writers, as a rule, aren’t the most sociable people in the world. They need hours of solitude if they’re to produce something worthwhile. Roth was a well-integrated and sociable person in his years as a child, teenager and young adult, and made many friends in college. Some of these friendships lasted until the day he died. He survived a tumultuous marriage to an older woman he met when he was only 23 and entered into a long-term relationship with actress Claire Bloom, during which time he lived mostly in London. He had other lovers and mistresses throughout his life. As he grew older, however, he became more and more of a recluse, spending long hours on his books, which grew in scope and importance to become indisputable masterpieces. According to writer Salman Rushdie, the growth and maturity reflected in these books were a direct consequence of Roth’s turning his creative beam from the obsessive self-analysis of his early works to the depiction and discussion of what lay around him, focusing on the bigger issues and themes of his beloved America. In his early 80s, he was perfectly happy living alone in his beautiful country house in Connecticut. When asked if he ever felt lonely, he replied, “Yes, sometimes, like everyone else,” but that the absence of friction – the inevitable result of contact and negotiations with other human beings – was something he never missed. It’s bliss not to have to cope with this any longer, he claimed.

The best way to get to know the real Roth – or rather, the Roth that matters – is by reading any of his 31 books. Immerse yourself in his world of masks without worrying too much about what’s real or imaginary. Engage in his game of mirrors. Appreciate his language and power of imagination. The life of any human being is composed of memories, so its account is never 100 percent reliable. We create and recreate reality all the time, so why expect anything different from a man who earns his living writing fiction? You will never get to his core because it’s impossible to grasp, being unpredictable and transient.

Jorge Sette

Love is always in the air, even in these difficult times of COVID-19. To help our blog followers make a decision on what to read next during the quarantine, we’ve selected 5 classic Latin American stories (three novels, a novella, and a play). These are stories in which love and passion (and their inseparable counterparts: hatred, vengeance, and violence) play a key role, though they do not necessarily fit the paradigm of romantic works. Let’s explore them.

Kiss of the Spider Woman, by Manuel Puig

Argentina in the mid-1970s. The charismatic window dresser Molina (age 37, gay, sentenced to 7 years in prison) shares a cell with the political prisoner Valentin (age 26), who cannot forget the woman he left behind to serve the revolutionary cause. To fill up the void and boredom of their current situation, Valentin spends his waking hours either studying politics or listening to Molina’s retelling of his favorite films (they are usually romantic, black-and-white B-movies from the 1940s, featuring strong glamorous heroines he identifies with. Warning: the reader will get completely hooked on these melodramatic plots!). Slowly, a powerful bond develops between these two very different men. But can Valentin trust Molina? Or is he just a poisonous spider, weaving a dangerous web around Valentin, who’s entrapped by his captivating storytelling and generosity? Revolution, sexuality, male bonding and gender rights are the key themes of this unforgettable and moving tale of tales. In 1985, the novel was made into an acclaimed movie directed by Hector Babenco, featuring William Hurt, Raul Julia, and Sonia Braga.

Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, by Mario Vargas Llosa

Set in 1950s Lima, Peru, this is the story of Mario, age 18, a Law student and aspiring writer, who works as a journalist for a radio station. Two simultaneous events will have a sudden impact on Mario’s quiet and reserved life. The arrival in Peru of his divorced Bolivian Aunt Julia (the exuberant sister of his uncle’s wife) in search of a new husband, and the hiring by the radio station of the also Bolivian eccentric scriptwriter Pedro Camacho, whose hard-working habits and inexhaustible creativity will become sources of inspiration to the young man. Mario and Julia – the typically irresistible older woman – start a puritanical romantic relationship, necessarily hidden from the rest of the family. Meanwhile, Pedro Camacho’s outlandish radio serials – whose plots, reproduced in prose, are incorporated in suspenseful chapters within the main narrative of the novel – take Peruvian audiences by storm, transforming the scriptwriter in an overnight celebrity. Hilarious.

Chronicle of a Death Foretold, by Gabriel García Márquez

The opening lines of this thrilling novella are among my favorite in all Latin American literature:

“On the day they were going to kill him, Santiago Nasar got up at five-thirty in the morning to wait for the boat the bishop was coming on. He’d dreamed he was going through a grove of timber trees where a gentle drizzle was falling, and for an instant he was happy in his dream.”

You may wonder how the author manages to keep readers hanging on to his every word until the last paragraph, since the ending of the tragedy has already been so openly given away. Well, the obvious reason is we are dealing with Gabriel García Márquez here. In his works, the plot represents only one among many fascinating elements, which work together in the creation of a whole literary experience. The characters, for example, with their idiosyncrasies and complexity, leap off the page. The language stands out, producing a hauntingly suspenseful atmosphere; the strength and relevance of the themes (at once local and universal) engulf the reader in a potent swirl of ideas and feelings.

This novella is basically a deep examination of the chauvinistic culture still very much ingrained in the region. Following the extravagant and lavish wedding celebrations, the young Angela Vicario is sent back to her parent’s home only a couple of hours after the ceremony, as her husband, the rich and powerful Bayardo San Román, discovers she is not a virgin (which will not allow him to get the necessary public validation by the shameful tradition of displaying the bloodied linen sheet as proof of the marriage consummation). The young girl’s twin brothers, Pedro and Pablo, take upon themselves to avenge the family’s honor. They will hunt down and kill the man who seems to be responsible for the girl’s doomed fate, the wealthy and good-looking Santiago Nasar. Surprisingly, as the narrator – a friend of the victim’s from their school days – collects interviews from the various inhabitants of the town to reconstruct the events and write the story decades later, he finds out that everybody seemed to have known in advance, one way or another, about the murderers’ plans: so how could they have failed to warn Santiago of his imminent death?

Of Love and Shadows, by Isabel Allende

The love story takes place in Chile during the military dictatorship of the 1970s and 80s. Francisco and Irene, the protagonists, have very different backgrounds. He is the youngest son of a Spanish anarchist, Professor Leal, who fled the Spanish Civil War with his wife, Hilda, and now, living in Chile, uses a printing press at home to produce leaflets promoting his political views. Francisco is involved in the clandestine leftist resistance, helping people hide and cross the border to escape the tentacles of the Political Police. Looking for a job as a photographer, Francisco meets Irene, a charismatic upper-class heiress who works as a journalist for a women’s fashion magazine. Their initial friendship and camaraderie develop slowly into passionate love, as Irene’s political awareness also matures. They finally realize they can’t live without each other.

However, when they discover an abandoned mine packed with corpses of desaparecidos (missing people, killed by the repressive military regime), they must embark on a political mission that will change their lives forever. The novel’s themes remain relevant, as political upheavals continue to shake South America in the 21st century.

Death and the Maiden, by Ariel Dorfman

This disturbing play in three acts (which has had productions in Chile, New York, and London, and was also made into a movie directed by Roman Polanski, starring Sigourney Weaver and Ben Kingsley in 1994) deals with confronting terrifying ghosts from one’s past.

Paulina Salas lives with her husband in an isolated house on the beach somewhere in Chile, nursing her psychological traumas from the recent past, when she, as a leftist militant, was imprisoned and tortured by members of the military dictatorship.

Times have changed: the dictatorship is over now and the nation is undergoing a healing process. Gerardo Escobar, her husband, has been appointed a member of an Investigating Commission that will look into the crimes against human rights perpetrated by the former regime. One night, however, he gets a flat tire and has no available spare. He’s rescued by Doctor Roberto Miranda, who’s also staying in a house on the beach, and gives him a ride home.

On the following night, Roberto turns up unexpectedly at Gerardo’s home, saying he just wanted to find out if they needed any more help with the car problem. On hearing the doctor’s voice, however, Paulina recognizes it. Although she could never see the man’s face in prison, she is sure he was the sadistic doctor in charge of her torture sessions. She is determined to take justice into her own hands, putting the doctor on trial in her own house… and she will enlist her husband as Dr. Miranda’s lawyer in the macabre plan.

If you have more suggestions on great Latin American literature, please write your comments below.

Jorge Sette.

For months, I tried to get an exclusive interview with Homer Simpson for Father’s Day. His PR representative kept turning me down but I didn’t give up. Then I had a lucky break. As Lisa, his daughter, was browsing through my blog Linguagem, she came across the article Stephen King’s The Shining: Like Father, Like Son (https://wp.me/p4gEKJ-1IL) and got interested. The PR rep had neglected to inform Mr. Simpson as to where the interview would be published. Lisa convinced her Dad how important it could be for his career to talk to Linguagem. Consequently, Homer immediately granted me an interview. He couldn’t have been more apologetic about his employee’s gaffe. Needless to say, she got fired.

The next day I flew to Springfield and, after a wonderful dinner with the entire family, I spoke to Homer. Below, you will find a summary of the insightful conversation we had about his life and the importance of fatherhood:

Linguagem: Mr. Simpson, how do you plan to celebrate Father’s Day with your family? Are you going anywhere fancy?

HS: What’s the point of going out? We’re just gonna wind up back here anyway.

Linguagem: I see. How do you feel about life in general?

HS: I’ve learned that life is one crushing defeat after another…

Linguagem: Do you follow any particular philosophy on how to educate your kids? Can you give us an example of how you discipline them when they are out of line?

HS: Now Bart, since you broke Grandpa’s teeth, he gets to break yours.

Linguagem: And what about when your boy reach puberty?

HS: …I told my wife how to go about teaching Bart how to become a man: The code of the schoolyard, Marge! The rules that teach a boy to be a man. Let’s see. Don’t tattle. Always make fun of those different from you. Never say anything, unless you’re sure everyone feels exactly the same way you do.

Linguagem: Hmmm. As a Dad, what are your hopes for your children?

HS: I believe that children are our future. Unless we stop them now.

Linguagem: Are you a religious man? Do you thank God for the great life and wonderful family you have?

HS: I’m normally not a praying man, but if you’re up there, please save me, Superman. But I remember saying on one particular occasion: Dear Lord, the gods have been good to me. As an offering, I present these milk and cookies. If you wish me to eat them instead, please give me no sign whatsoever…thy will be done.

Linguagem: What would you do if there were some kind of emergency with your kids?

HS: Operator! Give me the number for 911!

Linguagem: What is the best advice you could give to kids who didn’t accomplish what they had wanted to?

HS: Kids, you tried your best and you failed miserably. The lesson is, never try.

Linguagem: Do you consider yourself a good role model for your children?

HS: I think the saddest day of my life was when I realized I could beat my dad at most things, and Bart experienced that at the age of four.

Note: all Homer’s answers are actual quotes from the very successful and funny TV show. Homer may sometimes sound harsh, but he is a loving father and adored by his dedicated wife. Happy Father’s Day to all.

Jorge Sette